Today, efforts to shift the global economy away from fossil fuel-based energy and towards renewables are being affected by opposing forces. On the one hand, Donald Trump’s assault on clean energy and climate science has undoubtedly sent the wrong message to the many international energy companies who are reviewing (or relinquishing) their green energy commitments. On the other hand, renewable energy continues to be a cost-competitive energy source even compared to cheap coal, and the world now invests almost double the amount in clean energy as it does in fossil fuels, with China and the European Union driving these investments.

But energy transitions will always be contested, and two steps forward might be followed by one step back. For instance, China is still heavily investing in coal power, while Indonesia’s coal production reached record levels in 2024. This is because the energy transition can’t succeed simply by switching one energy source for another; the way we produce, distribute, and consume energy requires significant transformation into a much more flexible, decentralised, and smart energy system. This can only be achieved if stakeholders—mainstream society in particular—perceive this transition as necessary, fair, and equitable. Without this fairness, people might oppose the shifts and transformations we need.

With this in mind, the “just” element of energy transitions is more important than ever. But despite all the talk about just energy transition, few people seem to investigate what that actually means.

This is where our study hopes to provide suggestions for conceptual clarity, as well as giving a first overview of how justice is reflected in energy and development policies developed in Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries and China.

We developed an 18-indicator framework for just energy transitions (JET-18) drawn from academic sources and our own expertise as energy transition researchers (see figure 1).

Figure 1. The JET-18 framework for just energy transitions.

The indicators were grouped under eight themes, which included labour justice, environmental justice, structural reform, and energy justice, among others. We then used an artificial intelligence (AI) language model to sift through 74 policies—mostly energy policies, such as power development plans, but also development policies—from seven ASEAN countries and China, and extracted quotes that alluded to or reflected these 18 indicators. We then scored those policies for each indicator on a simple scale of 0–2, where 0 meant that no consideration of an indicator was found in the policy and 2 represented a verifiable and concrete target for the indicator.

Scoring policies is an established method in policy analysis, but we are aware of the shortcomings of qualitative scoring and mindful of the limitations of our policy sample, which included only those policies written in (or translated into) English. Nevertheless, we were still able to extract valuable information about how justice elements are reflected in regional policies.

The good news is that all our 18 indicators were reflected in our policy sample in one way or another. The less encouraging news is that there is ample room for improvement.

No policy scored above 50% of the maximum possible score, meaning that the JET-18 indicators were found only rarely and no policy contained provisions for all 18 indicators. Equally concerning, across countries, several key indicators of facilitating a just energy transition were insufficiently represented in the policies. For instance, policies rarely mentioned provisions for workers to receive unemployment benefits should they lose their job in the fossil fuel industry, regardless of the country. Also rarely found across the policies were provisions for recycling and reusing waste from renewable energy and provisions that recognise the land rights of local communities. Provisions for empowering people to become stewards of the energy transition (for example, by allowing them to generate electricity and sell it back to the grid or by supporting their investment in communal energy projects) were also only rarely found. Even when an indicator of justice was reflected in the policies, most of the time there were no concrete or verifiable objectives pertaining to the indicator.

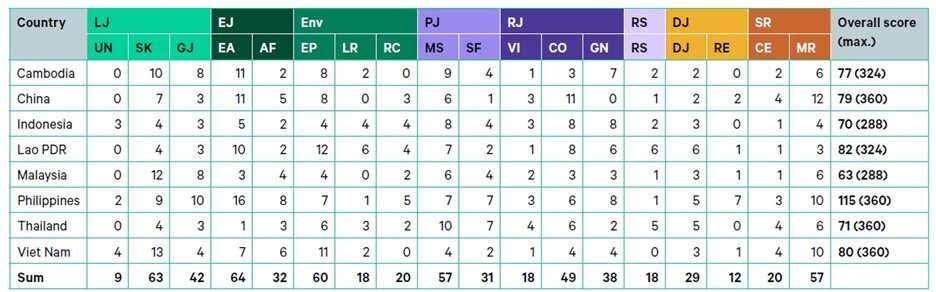

Table 1. Results from the policy analysis: scores for the 18 indicators.

In Table 1, LJ=labour justice; EJ=energy justice; Env=environmental justice; PJ=procedural justice; RJ=recognition justice; RS=restorative justice; DJ=distributional justice; SR=structural reform. The sums in the rightmost column are the sums of all policy scores for each country, i.e. how much all the 8 to 10 policies scored. For example, all nine analysed policies in Cambodia combined scored 77 (out of a possible 324) [18 indicators × a maximum score of 2 × 9 policies]. The sums in the bottom row correspond to the total score for each indicator in all countries combined. For example, the indicator “restorative justice” (RS) scored 18 (out of a possible 144) [average of 9 policies × maximum score of 2 × 8 countries].

Despite the limitations of our study, the way forward becomes clearer:

1. Policy-makers should consider more thoroughly what “just transition” actually means and how they can cater to the proposed indicators in their policies by including concrete and verifiable objectives.

2. We need a more comprehensive understanding of how justice is reflected in policies. More policies should be analysed, ideally including policies drafted in local languages.

3. While having good and just policies in place is a necessary first step, implementation is another important factor. For instance, many countries do have environmental protection provisions in their policy portfolio, but implementing and enforcing those policies is often a more complicated matter. Therefore, translating policies into concrete actions and enforcing their provisions is key for a just energy transition.

Emphasising the “just” element of just energy transitions is not a “nice to have”, but is fundamental to the success and the scaling up of energy transition efforts. Energy transitions don’t automatically become just, as there are pitfalls along the way that could increase inequality, decrease access to energy, or allow some people to reap the economic benefits while others gain nothing or even lose out. And if developments are perceived as being unjust or detrimental to people’s economic status, people will not be able to help transform the energy system—or, worse, they will oppose energy transition actions flat out. Only by having a broad coalition of stakeholders who can reap the benefits of transforming the global energy system will the transition succeed.

It is therefore necessary to not only invest heavily in renewable energies but also make sure that justice is at the centre on the road towards a low-carbon energy system that contributes to a more socially and economically just society.

Stefan Bößner is a research fellow and the policy lead at the Stockholm Environment Institute’s (SEI) Bangkok office, where he works on just energy transitions, low-carbon innovation, and science-to-policy pathways.

Huiling (Mia) Zhu is a Research Associate at the Stockholm Environment Institute’s Bangkok office, where she works on just energy transitions and climate finance.

Stay Informed and Engaged

Subscribe to the Just Energy Transition in Coal Regions Knowledge Hub Newsletter

Receive updates on just energy transition news, insights, knowledge, and events directly in your inbox.